A lot of writer’s blogs give writing advice.

A lot of writer’s blogs give writing advice.

I’m not entirely comfortable with this.

Never mind the whole question of at what point in your career are you really qualified to offer advice on the art and craft of writing. I really couldn’t say. But I notice that people often pass around the same “lessons” on how you should do things. Frequently this kind of teaching is repeating what someone has told them, rather than from experience.

We used to run into this kind of thing with Kung Fu.

I studied and helped teach some of the Taoist arts for about 15 years. The three major internal arts, Tai Chi, Pakua and Hsing-I, are often presented as arts for lifetime practice. Like most arts, it takes time to learn the forms, the movements and the rules. Then you practice. Over time, you make it your own. Like most Taoist approaches, results are measured by your internal barometer. There are no real external markers for success.

Of course, our society isn’t much for long-term anything and we’re all about external markers of success.

Thus the weekend seminars where people learn Tai Chi, and then go teach it. To me this is a lot like passing along writing lessons that aren’t from actual experience.

So, I rarely give writing advice, except to talk about an experience.

I’m breaking that rule today.

I notice a lot of people complain about getting stuck in their manuscripts. Always at the same place. For some it’s starting, for others finishing. A lot of people hate the middle.

This isn’t just about writing a novel, it’s about dealing with all of life.

So, I give you the cycle of the five elements here. If you’re familiar with this sort of thing, you’ll know the principles of the five elements form the foundation for much of the Oriental philosophies. Yeah, I’m lumping India in with the Orient.

Here’s a nice simple chart. There are some abysmally complex ones out there, but we’re keeping this simple. So a basic way to read this is, water grows wood, wood burns into fire, fire reduces to ashy earth, earth transforms into metals and metals reduce back into simple water. Don’t get caught up in the logic – suffice to say their idea of “metal” is a bit different.

Instead, look at it this way.

No, I’m not just randomly substituting. Birth is like water, like the primordial sea that is the beginning. Wood is growth, like the forests, plants and vines covering the world. Maturity is the fire, the balance between growth and decline. It can be nurtured to last a long time or can be a flash and disappear. Earth is the decline, the sinking back of growth into the ground. Death is the endpoint that cycles back into birth.

That’s one of the points. This isn’t a straight line; it’s a circle. Death makes birth possible.

You can match this to the seasons, too: Spring is birth, followed by summer, a moment or forever of midsummer, the decline of autumn and the death of winter – which gives way again to spring.

So, at last, my point:

We can apply this to writing our stories and novels. The analogy should be clear by now. You have your beginning that sets the stage, the growth of the story, the middle, which often contains the turning point, then the the decline, the wrapping up of the story and the ending.

Most of us are better at some points in the cycle than others. In our hearts, we already know which parts of life we struggle with. Some can start things; some can’t end them. Some get stuck between growth and decline with no understanding of what to do with it.

One writer-friend of mine has a hard time with decline, for example. She hates to let things go. Once they’re already declined, she can let them go into death, but she has a tendency to try to keep things from declining. That’s where she gets stuck.

Me? I don’t like killing things off. I like things to last forever. So I practice. I try to embrace the end of things in my life. Kill it off and let it go.

I’m not necessarily good at it.

Ah, but the birth that follows is a glorious thing.

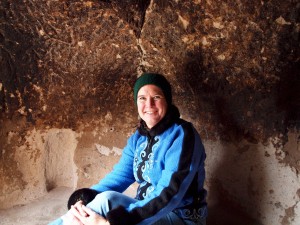

A photo of me at Bandelier National Monument this last weekend. The cliff dwellings are particularly fun to see, since you can climb up into them.

A photo of me at Bandelier National Monument this last weekend. The cliff dwellings are particularly fun to see, since you can climb up into them.