Fun news on covers and Italian rights – along with some info on how selling foreign rights works. Also, my recent experience with a published book contest and how negative comments can be devastating.

RITA ® Award-Winning Author of Fantasy Romance

Fun news on covers and Italian rights – along with some info on how selling foreign rights works. Also, my recent experience with a published book contest and how negative comments can be devastating.

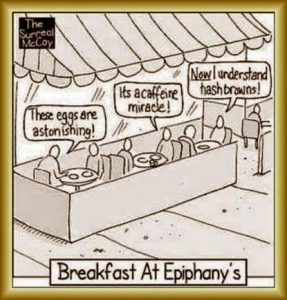

I used this cartoon in an online class I’m teaching on using the sexual journey as a tool for character transformation. It cracks me up every time, so I thought I’d share here.

I used this cartoon in an online class I’m teaching on using the sexual journey as a tool for character transformation. It cracks me up every time, so I thought I’d share here.

The other day I finished judging some entries for an unpublished manuscript contest hosted by a writer’s organization I’m part of. I judge a number of contests each year, both for published books and these unpublished manuscripts. In fact, this year I’m coordinating one for my local RWA chapter, The Rebecca, so disclaimer there.

I passionately believe in hosting these contests, not only because they make excellent fundraisers for programming we couldn’t otherwise afford. They give an opportunity to aspiring writers to both gain feedback on their manuscripts and potentially get them in front of agents and editors who might otherwise be difficult to access. When I was shopping my first novel, I entered a lot of these contests, and it was great to have those venues.

That said… this recent experience gave me pause.

For this contest, authors submitted the first twenty pages of a manuscript. For The Rebecca, it’s the first 5,000 words, which works out to slightly less. At any rate, of the five entries I evaluated, two showed great promise, with beguiling premises and worlds, but both crammed WAY too much into those first twenty pages. To the point that I became overwhelmed.

Contest veterans will know this, but part of what’s happening here is that the writers know they’ll be evaluated according to a score sheet. Most contests ask if the internal and external conflict is apparent – for both the hero and heroine in romance – and if character motivations are clear. These are good things to evaluate and yet – very few books lay out ALL of the conflict and character motivations in the first twenty pages. Particularly if there are two or more point-of-view (POV) characters. In fact, they really shouldn’t do that because it mucks up the pacing of the novel.

Which is exactly what happened with these entries. They became to my eye – which is admittedly one reader’s opinion – almost kaleidoscopic in the rapidity of the scene shifts and changes of POV. I understood why the authors felt they needed to do this, but I ended up scoring down for categories like pacing and clarity of various characters.

What’s most concerning is – they didn’t read like the actual openings of novels. Since a huge piece of the contest involves sending the finalists to the final judges, agents and editors, to rank and hopefully want to see more of, possibly to acquire, I worry about this tendency. As a contest coordinator, I’m wondering what we can do about it.

The upshot is, for all of you trying out your manuscripts this way – please keep this in mind. The opening of your novel should read at the pace of an actual novel, not a construct created to satisfy all the points ticked off by a contest judge.

Anyone have thoughts on this, particularly how to address it?

To celebrate that THE TALON OF THE HAWK won Best Fantasy Romance of 2015 from RT Book Reviews, I got this amazing tattoo of Ursula’s sword. I’m thrilled with how it turned out. (Freshly finished and a little red here – it looks even better now!)

To celebrate that THE TALON OF THE HAWK won Best Fantasy Romance of 2015 from RT Book Reviews, I got this amazing tattoo of Ursula’s sword. I’m thrilled with how it turned out. (Freshly finished and a little red here – it looks even better now!)

If you haven’t yet signed up for my newsletter, one went out today with an exclusive, never-seen-elsewhere, juicy deleted scene from TALON. If you sign up today, you can still see it. Yes, I’m totally luring you. Is it working?

You’ll see this in the newsletter (hint, hint) – Kensington is sponsoring a Goodreads Giveaway of 25 copies of THE PAGES OF THE MIND. Hie thee hence to enter!

Finally, I’m over at Word Whores this morning, setting forth the question of whether published books contests that require an entry fee, such as RWA’s RITA Awards, have less integrity than those where books must be nominated, such as SFWA’s Nebula Award.

We haven’t had a sunrise pic in a while. Sign of the season, I suppose, when my regular wake-up time now precedes the sun’s. Alas for that.

We haven’t had a sunrise pic in a while. Sign of the season, I suppose, when my regular wake-up time now precedes the sun’s. Alas for that.

I’ve been crazy busy lately wrapping up The Rebecca Contest. This is my local chapter LERA’s contest for unpublished manuscripts. (Our finalists are listed here.) For some reason, in an era of declining contest participation, our numbers went up this last year. This is the second year I volunteered as the Contest Coordinator, so it’s given me an interesting perspective on the industry.

I shouldn’t fling that “for some reason” out there, because I do have a pretty good idea what made this contest attractive to aspiring writers. One is that we made a serious effort to have final judges who are solid industry professionals who are both actively acquiring new authors and who are not easy to access for most writers. That’s what I wanted for my work when I was entering contests, and that’s what we try to get for our contestants.

Second is that it’s noteworthy that it’s a contest for unpublished manuscripts – not unpublished authors. This means that authors who’ve already published can participate as long as the manuscript in question is not under contract when they enter the contest.

This aspect brings up an important point about our industry that I think can get overlooked. It used to be that getting published was the sinecure, the lifetime career that ended with the literary equivalent of a gold watch and a generous pension. Now, just as those days of the lifetime career with one company have given way to an average of 5-6 careers in an American’s life, getting a contract for that first book, or even that 2- to 3-book series is no longer a guarantee of anything. The market is tough, the stakes high and publishers are frequently kicking authors to the curb whose books/series don’t perform to high expectations. And it’s a sad irony that the writer is now not that enticing creature, the “debut author,” who seems to be as avidly sought as the proverbial beautiful, young virgin.

How does an author circumvent the scarlet letter of less than bestselling numbers on a previous effort? The anonymity of a contest works pretty damn well.

Of course, this means that our contest had incredibly stiff competition. In two categories, in particular, the finalists were fractions of a point apart. This is the most interesting part to me. Can anyone guess which were the two most competitive categories? The five were:

Historical Romance

Category Romance

Paranormal Romance/Science Fiction Romance/Urban Fantasy

Young Adult Romance

Contemporary Romance

Did you all make your guesses?

YA and Paranormal. Both had the most entries (though Contemporary only had three fewer entries than YA) and both had the closest finalists scores. In Paranormal, the three finalists all had perfect average scores. (Each entry is judged by three people, at least one a published author, the lowest score of the three is dropped and the two highest scores averaged.)

I think this reflects the marketplace, too. YA and the speculative fiction takes on romance continue to sell well. The competition out there is fierce.

What lesson do we extract from this? I’m curious to know what you all think. Does the savvy writer focus on those less-competitive sub-genres, hoping to stand out as a shiny fish in a smaller pond? Or does she set her sights on upping her game and hope the high tide floating all those ships in the popular sub-genres will sweep her along, too?

Of course, that’s pre-supposing that any writer really chooses what they write…

This morning in the Water Cooler, we had an interesting conversation about contests and a pitfall I’d never considered.

The Water Cooler is a chat room on the website of our Fantasy, Futuristic and Paranormal Chapter. One of our board members is an amazing web designer and she created these various chat rooms for us. The Water Cooler is for hanging out while you write. Sometimes we do timed sessions and then report back word counts or pages edited. Sometimes we throw out problems we’re struggling with, for feedback.

Sometimes we just yak.

This morning, one gal mentioned that she wasn’t working on her WIP — lingo for Work in Progress — but instead doing penance and judging a contest entry. Penance because she’d failed to notice that one of the entries given her to judge was the exact same entry she’d judged for another contest the week before. These are for our chapter On the Far Side contest and everyone is supposed to be done judging by tomorrow.

She turned the entry back in and took another because she “would have had to write all the exact same comments.”

So, it’s an interesting thing. So many RWA chapters sponsor contests that the market is arguably flooded. And yet, these are opportunities unmatched in the business, that you can get your work in front of agents and editors who serve as final judges, but who won’t accept unsolicited submissions. Some people get caught up in collecting contest finals and wins (one group keeps count and actually gives the person with the most finals in a year an actual TIARA — yes, these are all women). But really, the point is that this is a chance to get your manuscript that much closer to publication.

The real prize.

The editors and agents serve as final judges, meaning that they judge the finalists. As determined by the chapter members who volunteer to judge. And sometimes people from outside the chapter, if the chapter in question can’t get enough volunteers.

Now, many people in RWA belong to several chapters — maybe a local one or two and a couple online groups. So there are two or three contests you’ll be hit up to judge right there. More if you’re feeling generous and volunteer to help another group. The pool of people submitting to the contests is largely this same group and they usually hit as many contests as they can, to maximize their chances.

There’s a word for this syndrome.

MFA programs have been accused of producing literary clones. (I tried Googling “MFA Syndrome” to give you a good link to an article, because I know I’ve read a couple, but all the hits were in other blog posts. Hmmm….) The academic/MFA environment produces literary writers who get university posts to teach MFA programs.

Right! Incest.

And we all know what the product of incest is. Lethal mutation at worst; reduced heterogeneity at best. Reduced heterogeneity in biology leads to weaker individuals, for those not up on their genetics and evolutionary biology.

There have been complaints that the contests are past their prime. That the agents and editors don’t request full manuscripts as much. That they aren’t making as much money for the chapters.

Maybe we should think about doing something different.

I realize my title is probably dating me.

There’s a whole couple of generations who don’t understand references to German judges. Or who think Mikhail Baryshnikov is just a cute guy on Sex and the City; they’re surprised to hear he’s a dancer and ask what kind. I swear to God I’ve had this actual conversation. I have witnesses. They didn’t understand about Political Asylum either, or why he might have claimed it.

The German judge, for those who didn’t watch the Olympics in the 70s and 80s refers to the international panel of judges scoring the various Olympic events. There was often a perception that the German judge was a) tougher and b) inclined to mark down competitors from the non-communist countries. For accuracy, we should really say the “East German judge,” but idioms aren’t about accuracy.

There’s been an interesting conversation on the Fantasy, Futuristic & Paranormal writers loop the last day or so, about contest judges. I’ve written before about the RWA chapter contests, so I won’t reiterate here. But the way it works is you generally get scores from two or three judges. In many contests, if the point spread exceeds a certain margin, a discrepancy judge is called in and the lowest score is dropped. The idea is to account for reader preferences, which can really affect scores. For example, on a recent contest I entered, one judge gave me a perfect score of 100 (with comments that it was so splendid she couldn’t gush enough) and another judge awarded me a 54 (with a snarky comment that beastiality is not an appropriate subject for a romance.)

One got me; one didn’t.

In the real world, this would translate to a person who would buy my book and one who would burn it. Fair enough. The common wisdom is that these kind of splits result from having a “strong voice” — readers tend to love it or hate it. All of this is lead-up to using one of my favorite examples, from country music. (Yeah, you saw that one coming, right?)

I heard this story on NPR many, many moons ago, but it’s always stuck with me. They were discussing the perception that country music radio stations had become less, well, interesting. It turns out that there had been a huge study where “they” looked at what caused people to change the radio station — anathema for advertising, of course. They found that people changed the station, shockingly enough, when a song they hated came on. So, it seemed simple: don’t play the songs people hate. BUT, what the studies showed is that the songs people rated as most hated were also rated most loved by an equal number of people. Where people converged was on the songs that they neither loved nor hated. More importantly for radio, when a song played that a person neither loved nor hated, they were likely to let the radio station play on.

Thus country music programming went to playing music that the vast majority of people neither loved nor hated, playing innocuously in the background, exciting nothing untoward.

I’ve seen this play out in writing workshops, too. Half the class will love a particular scene and half will insist it ruins the piece and must be removed. The profound emotional reaction means the writer has hit on something, but it takes courage to accept that for every person who loves what you wrote, someone else will hate it.

And it’s tempting, especially in genre, where people hope to actually make money with their books, to write the thing that will sell to the most people, innocuous and exciting no untoward responses.

Then again, it can be a little satisfying, too, to throw a little bestiality in the way of the book-burners.

I’ve been editing my novel. Not for the first time, naturally. I finished it almost exactly a year ago and have edited the work several times since.

Right now, though, I’m whittling down the first 30 pages. In genre fiction — maybe all kinds, I don’t know — much rests on the first 30 pages. Contests generally ask for it (or the first 20 or 25, if they’re chintzy), because agents generally ask for that. Then hopefully they ask to read the whole thing.

But everything really hinges off of the first 30 pages. They’ll argue it’s a Blink thing, that a good agent or editor knows within a few sentences if the work is what they can market. Or rather, they know right away if it’s NOT. What this means though, is there’s no room for leisurely introductions or backstory. An editor at the RWA convention complained of writers who tell her the story “really gets going in the third chapter.” That, she said, is where the story should start.

Okay, I can see this. That a genre novel’s glory is its ability to sweep you away. In our increasingly impatient society, there’s little patience for the slow build. Selling books is selling excitement. Capture the reader on the first page and you’ve sold the book.

What I’m noticing as a reader, however, is how many books start off great and completely fall apart. Sometimes the first three chapters promise something that vanishes or was never really there. And the second half of the book is frequently terrible. To the point that I wonder if the editor ever read the second half.

And then I wonder, do they care? Is the market such that all the emphasis is on selling that book. Mabye it’s become immaterial whether the reader will then buy or borrow that author again.

Not that I’m not playing the game. My book is one of those where the exciting action kicks in around Chapter 3 or 4. I felt like the slow build-up was important, but I’m capitulating. I’ve condensed 60 pages into 30. No point, I figure, in holding onto the perfect opening to an unpublished book.

A lot of what goes in that kind of slash-and-burn edit is description. A (terrible) contest judge recently slammed me for too much description, which she compared to Anne Rice. The judge invited me to recall how much people hated how she’d describe the wallpaper. I’m thinking, uh, Anne Rice? Multi-million dollar best-seller, Anne Rice? One of my favorite authors before she went off the deep end, Anne Rice? Oh no, don’t write like she does!

But, I concede to the gateway and have cut cut cut. My delete key is dripping black font. I really hope, though, that the rest of the story satisfies. Perhaps a lean, mean beginning can lead to a meaty repast with a lovely, fatty, overblown dessert at the end. In a room with gold, flocked wallpaper…