RITA ® Award-Winning Author of Fantasy Romance

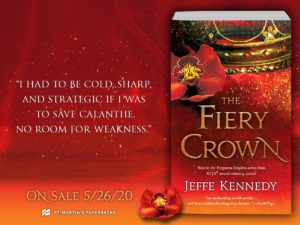

If you love some Romance with or alongside your SFF, my publisher is doing this fab giveaway of new releases to celebrate Romance Awareness Month! Note that my book, THE FIERY CROWN, is included 😀

Our topic at the SFF Seven this week is “Resurrections: What trope/theme did you think (or wished) had “died” only to be recently resurrected?” Come over to learn why I’m liking baked goods over guns.

Yes, this is a leftover Christmas pic, but I just dug it out of my camera and loved it. I was out taking sunset pics and noticed Jackson watching me from the window. I didn’t realize at the time how I caught the reflected sunset, along with my own. So much of what I love about my home in this one photo.

Yes, this is a leftover Christmas pic, but I just dug it out of my camera and loved it. I was out taking sunset pics and noticed Jackson watching me from the window. I didn’t realize at the time how I caught the reflected sunset, along with my own. So much of what I love about my home in this one photo.

I’ve been mulling lately about the trope of the Clumsy Heroine. For the most part, I don’t want to call out specific books (though I’m sure you can think up several offhand), but I will cite Twilight as a well-known example. For the record, I’m a fan of Twilight. In fact, I blogged just last week about my reasons why.

Bella, the heroine of the series, begins the first book as ridiculously clumsy. To the point that this is one of the most frequently leveled criticisms of the book. Even those of us who love the book and series roll our eyes over that. She’s so clumsy that she staggers into life-threatening danger at every turn – requiring the hero, Edward, to repeatedly save her. It gets so bad that you begin to wonder why she didn’t get killed playing in traffic before the age of five.

Now, Bella is irritating to many readers for a number of reasons, most of which have to do with her not feeling like a fully formed human being. She’s subject to the vicissitudes of fate, not an assertive person, seems like a puppet at times. There are arguments that she’s “empty” because she’s essentially an avatar for the reader. The reader inserts herself – and her own personality – into the glove that is the protagonist. Arguably this is part of what makes the book and series so compelling. But what about the clumsiness – what purpose does that serve?

I’m going to suggest that making a heroine clumsy is shorthand for creating a character who has not yet come into her evolved state. She hearkens back to the stage that most of us go through, that awkward adolescence where we seem to be able to do nothing right, whether we’re blessed with physical coordination or not. Even in the naturally athletic types, the growth spurts of our teen years can create situations where our limbs out pace the nervous system, creating dissonance in movement.

Another way of saying clumsy!

However, this stage doesn’t last into adulthood (if all is well) and we rarely see male protagonists with this syndrome, if ever. I did a quick survey in the SFWA chatroom – thanks all! – and the only exceptions we came up with are ones like Thomas Covenant, who has an actual chronic illness (leprosy); ones like Daniel Bruks in Peter Watts’ Echopraxia, who’s arguably only socially awkward; ones where the effect is intended to be humorous like Dirk Gently; or with the pervasive bumbling sidekick. The latter exists mainly to contrast with the ultra-competent hero.

I’d submit that readers wouldn’t tolerate a clumsy hero. So, why the clumsy heroine?

I don’t like the trope because I do think it’s shorthand for that raw emotional state of feeling inadequate. The clumsy heroine has not yet grown into graceful womanhood – despite her age – and requires (sometimes repeated) rescuing by the hero. It feels like lazy writing to me.

Does anyone LOVE the clumsy heroine thing? Clearly it’s been a successful trope, especially in romance. Arguments in favor?

Spring definitely begins in March here in Santa Fe. I spent a few hours sitting outside reading with my coffee in the sunshine this morning. Lovely!

Spring definitely begins in March here in Santa Fe. I spent a few hours sitting outside reading with my coffee in the sunshine this morning. Lovely!

This week at Word Whores, we’re discussing our favorite genre tropes. Since we get to pick the genre and I write in three at the moment, I’m talking about one from each. Also, since I’m the topic-kickoff girl, I’ll take on the job of defining “Trope,” for those who aren’t familiar.

I’m over at Here Be Magic today, talking about a possible pitfall in writing heroines in fantasy novels.

I’m over at Here Be Magic today, talking about a possible pitfall in writing heroines in fantasy novels.

I’ve been reading a lot of books lately that I wouldn’t normally pick up.

I’ve been reading a lot of books lately that I wouldn’t normally pick up.

That’s because I’m judging for the Romance Writers of America (RWA) RITA awards. This is the romance genre’s version of the Hugo or the Oscar. Yeah, there might be some out there already snorting in disdain, but for our genre, this is one of the highest awards you can get. The first round is entirely peer-judged. As in, if you want to enter your book for the RITA, then you must judge. Thus, in mid-January, I received eight novels to read by the beginning of March.

We do get to pick categories, but otherwise I am reading books by authors I have never read before. All of them are a bit of a stretch from my normal pleasure reading. We’re asked to judge the book entirely on its quality and not whether or not we enjoy that particular kind of story, which is also a different lens.

It’s been interesting. And I’m over halfway through my pile, amazingly enough.

One of them is a new author discovery for me now. I gave her book a perfect score and look forward to reading more. Another, in a sub-genre I rarely read, I ranked very high. I don’t know that I’ll pick up her books again, for myself, but I could recognize how well she executed her craft.

One book, though written decently, failed as a romance, in my opinion. Oh, she had all the plot points in there. She faithfully followed the tropes, but they continued to feel empty to me. Contrived, even, which romance is so frequently accused of being.

So, here’s where I make a leap into a series of assumptions. I’m theorizing and obviously have no hard data to back up my ideas here.

It’s no secret that the romance genre is making big bucks these days. A fact that seems to seriously annoy all those who consider romance not worthwhile. Latest stats from RWA: $1.36 billion in sales each year, the largest share of the consumer-book market, more than a quarter of all books sold are romance. What writer doesn’t want some of that pie?

More and more, I’m seeing writers of other genres coming over to the romance field, to pump up their sales. Or adding touches of romance, in order to sell it on that shelf. And sure, sometimes this is the work of the publisher or marketing department, trying to slide in under that umbrella.

The thing is, it’s difficult to wield a trope you don’t love. See, a trope is like a cliché or an archetype. They can be powerful devices or cardboard dummies. A good romance embraces the full emotionalism of people coming together, with all the silliness, hearts, flowers, flying cupids, spats, passion, grand gestures and breathless, intimate moments that implies. It’s not easy to write clichés in a new, vivid and heartfelt way. But if a writer doesn’t tap into that deep store of energy that fuels the tropes in our hearts and minds, then all of that becomes cliché in the worst possible sense.

All of us romance readers love to giggle at the tropes. There are great blogs out there that encourage these discussions. We laugh at the impossibly virginal, feisty heroine and the alpha-male hero who also cooks and loves to brush her hair. And yet, when it’s done right, we also sigh in dreamy delight, and follow their story with fervent attention.

Why? Because the author takes the tropes and breathes life into them.

That doesn’t happen if the author, deep-down, doesn’t respect the tropes.

We might poke fun at the tropes like we roll our eyes at our husbands not being able to find anything without us, but if someone else makes out like our husbands are worthless? Oh no no no.

Use the power of the trope, young author.

But beware of taking it lightly.