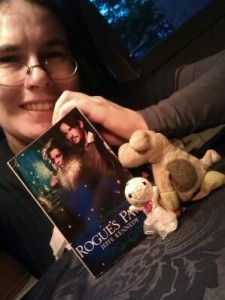

Love this photo from Carien, Sullivan McPig and Voodoo Bride – all hugging on their copy of Rogue’s Pawn. I might not have visited The Netherlands, but my books have!

Love this photo from Carien, Sullivan McPig and Voodoo Bride – all hugging on their copy of Rogue’s Pawn. I might not have visited The Netherlands, but my books have!

Many of you know I lived in Wyoming for a long time. I went there for graduate school, fell in love with David and ended up staying more than 20 years. Wyoming is an interesting place to live, landlocked in the middle of the country, with the smallest population of all the states. A lot of it is beautiful and a lot isn’t. But the people who live there have a fierce pride of place. There’s a certain mystique to being a resident, to combatting the ferocious winters and going without the luxuries other communities enjoy. It’s tied in with the Western Myth, the hero as a cowboy, the rugged loner and frontiersman.

When I met David – a Wyoming man, born and bred – he would sometimes comment contemptuously about the “Wyoming Wannabes,” the people who moved there wanting to be part of the mystique. There were people like this, who left the big cities and came to Wyoming thinking they’d become the Malboro Man. One writer friend pointed out that it was the only place she’d ever lived where people identified themselves by how long they’d lived there. She was right – everybody knew their length of residency and offered it up as their Wyoming cred, the longer, the better.

And, if you hadn’t been born there, it didn’t matter how long you’d lived there – you were never a “real” resident.

I think of this when I hear someone complain about another “mining a cultural tradition.” It’s this idea that a culture – or a place or a myth or mystique – is somehow the exclusive property of one group of people. On a panel I moderated at World Fantasy Con in 2012, the Australian author Sean Williams spoke at some length of being very aware of not inadvertently mining the aboriginal culture for stories or mythology in any way. I read much of this same criticism (among heaps of others) about Miley Cyrus’ performance at the Grammys this year, and how she was appropriating black culture.

It seems to be this sense that a minority or oppressed group has something precious, that should not be stolen by an imperialist culture.

What bothers me is, who decides what’s part of human culture or a place that anyone can enjoy and what belongs to only one group?

When I was a teen, I once told some family friends that I didn’t feel much patriotism for the United States as a whole, but that if my hometown of Denver was attacked, I’d fight to defend it. They were very interested in that and said they wondered if it was because I hadn’t lived much of anywhere else or traveled much. In many ways, they were right – as I’ve grown older and lived more places, my sense of the world has grown much broader. Many places are special to me now. I think about this in science fiction stories sometimes, that a day will come when we’ll identify as being “from Earth,” not just one city, state, or country, but the whole planet.

From that perspective, isn’t human culture all one culture?

I confess that it bothers me that, as a storyteller, I’m to keep my thoughts out of some mythologies. That they somehow belong to someone else, as their exclusive property. I suppose I believe that shared racial memory means among all human beings, not just the Irish/Scot/French/Dutch melange I can genetically lay claim to.

So, I’m curious to know what you all think. Is there a line that shouldn’t be crossed? And, if there is, how and where should it be drawn?