Our topic at the SFF Seven this week is our worst ROI ever. So many to choose from!

ROI is industry shorthand for Return on Investment. It’s basically a calculation for financial health of a business. I looked up the origin and found out that Donaldson Brown created the term.

As the Assistant Treasurer [of DuPont] in 1914, Brown developed a formula for monitoring business performance that combined earnings, working capital, and investments in plants and property into a single measure that he termed “return on investment.” It later became known in academic and financial circles as the DuPont Method (or Model) for Return on Investment. The measure was widely taught in business schools and adopted by many companies as a means of benchmarking the financial health of their products and businesses.

That’s interesting, because I wondered if it was an old model. Turns out it’s over a century old!

Also, the term comprises much more than I think most writers mean when they use it. When I hear writers talk about ROI, it’s always whether a particular effort – a conference, buying an ad, buying into an anthology – will be more expensive than the sales it generates. Many reduced it to the simplest math: “If I spend this much attending a con, will I earn more than that on sales of my books?” Often husbands are cited as putting forth this equation, usually as justification for wives not attending cons.

When asked for my opinion there (and sometimes even when NOT asked), I have always said that conferences of all types provide an intangible ROI. Networking and getting your books in front of people give long-term results that aren’t always quantifiable. Since I was doing a bit of research, I looked up if anyone thinks the DuPont Model for ROI is antiquated. Turns out there’s this:

We demonstrate that firms ‘assets are becoming increasing more intangible, and the traditional DuPont Analysis omits this crucial piece of a firm’s ability to generate profit.

Those folks are talking market equity, but it occurs to me that many authors looking at simple math and short-term sales are failing to account for the intangible value of building recognition for their work over the long term.

But I digress.

The topic today asks about my personal worst return on investment. Since I don’t really do the calculations – see above – I don’t know a precise metric. I can, however, share an investment regret. When my very first book came out, the essay collection Wyoming Trucks, True Love, and the Weather Channel, a friend of mine, Chuck, told me one of HIS great regrets was not buying a case of his first book. The first edition was worth a great deal and he was sorry not to have done that. So, I bought a case of my books!

Reader: I still have most of them.

See, my first book didn’t sell tons of copies and I have not become an NYT bestseller with a TV miniseries based on my books, unlike Chuck. He meant well, and I adore him for thinking that I would have the same trajectory, but I’m not C.J. Box, alas!

I suppose the key takeaway here is that there is no one size fits all advice.

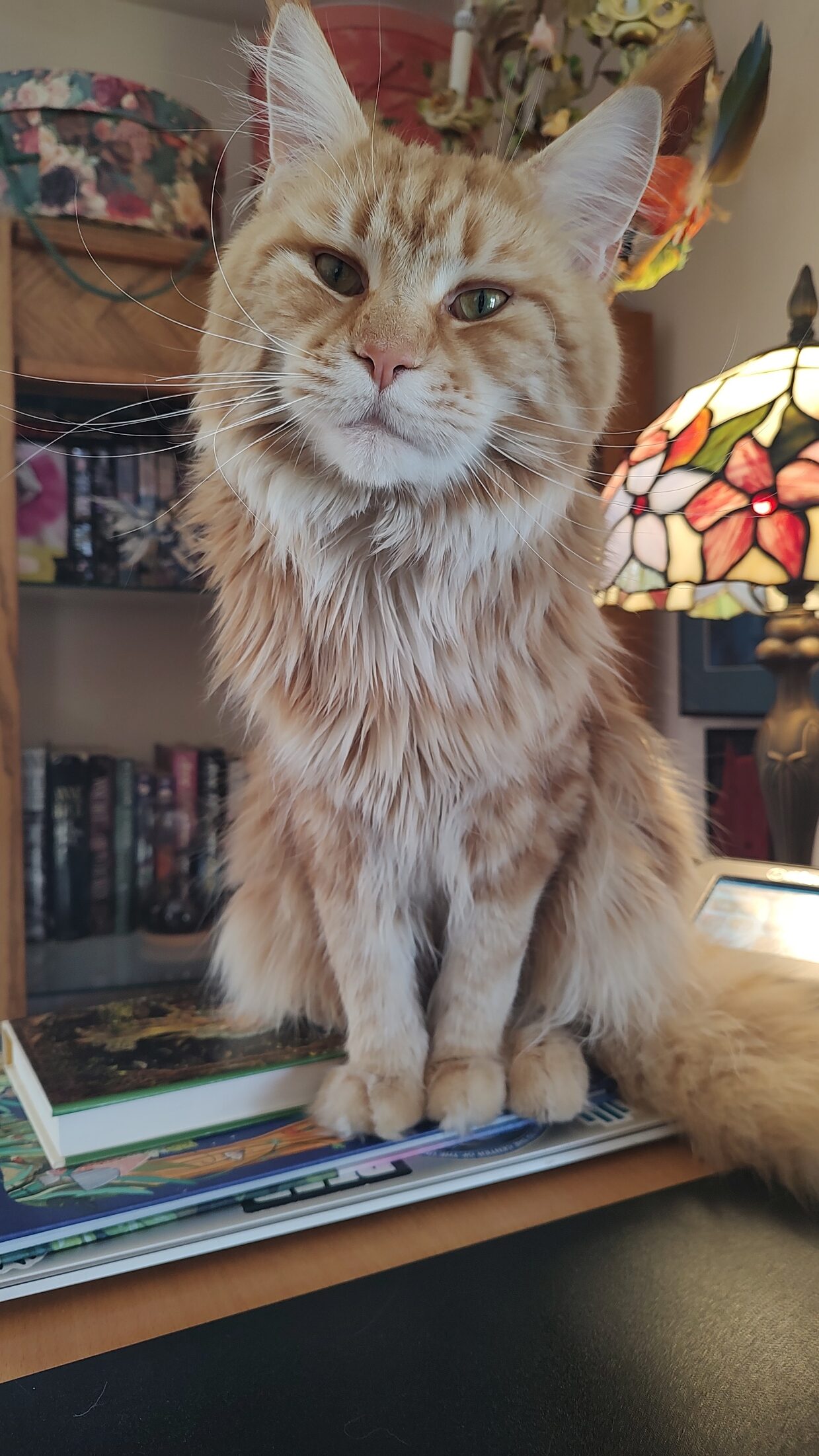

Also, that the ROI on cats is always solid.