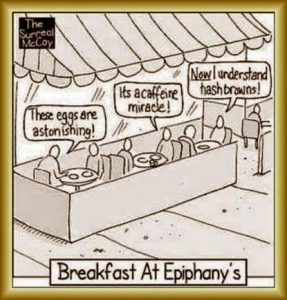

I used this cartoon in an online class I’m teaching on using the sexual journey as a tool for character transformation. It cracks me up every time, so I thought I’d share here.

I used this cartoon in an online class I’m teaching on using the sexual journey as a tool for character transformation. It cracks me up every time, so I thought I’d share here.

The other day I finished judging some entries for an unpublished manuscript contest hosted by a writer’s organization I’m part of. I judge a number of contests each year, both for published books and these unpublished manuscripts. In fact, this year I’m coordinating one for my local RWA chapter, The Rebecca, so disclaimer there.

I passionately believe in hosting these contests, not only because they make excellent fundraisers for programming we couldn’t otherwise afford. They give an opportunity to aspiring writers to both gain feedback on their manuscripts and potentially get them in front of agents and editors who might otherwise be difficult to access. When I was shopping my first novel, I entered a lot of these contests, and it was great to have those venues.

That said… this recent experience gave me pause.

For this contest, authors submitted the first twenty pages of a manuscript. For The Rebecca, it’s the first 5,000 words, which works out to slightly less. At any rate, of the five entries I evaluated, two showed great promise, with beguiling premises and worlds, but both crammed WAY too much into those first twenty pages. To the point that I became overwhelmed.

Contest veterans will know this, but part of what’s happening here is that the writers know they’ll be evaluated according to a score sheet. Most contests ask if the internal and external conflict is apparent – for both the hero and heroine in romance – and if character motivations are clear. These are good things to evaluate and yet – very few books lay out ALL of the conflict and character motivations in the first twenty pages. Particularly if there are two or more point-of-view (POV) characters. In fact, they really shouldn’t do that because it mucks up the pacing of the novel.

Which is exactly what happened with these entries. They became to my eye – which is admittedly one reader’s opinion – almost kaleidoscopic in the rapidity of the scene shifts and changes of POV. I understood why the authors felt they needed to do this, but I ended up scoring down for categories like pacing and clarity of various characters.

What’s most concerning is – they didn’t read like the actual openings of novels. Since a huge piece of the contest involves sending the finalists to the final judges, agents and editors, to rank and hopefully want to see more of, possibly to acquire, I worry about this tendency. As a contest coordinator, I’m wondering what we can do about it.

The upshot is, for all of you trying out your manuscripts this way – please keep this in mind. The opening of your novel should read at the pace of an actual novel, not a construct created to satisfy all the points ticked off by a contest judge.

Anyone have thoughts on this, particularly how to address it?