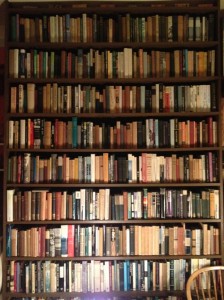

This is a photo from Amanda Palmer’s Tumblr, with the caption “books are home.”

This is a photo from Amanda Palmer’s Tumblr, with the caption “books are home.”

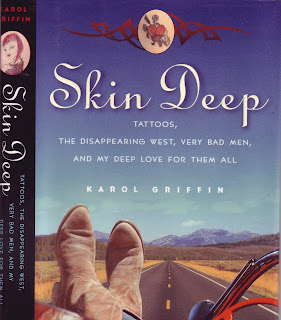

When I saw it go by in my Tumblr feed last night, I thought that I glimpsed the distinctive spine of a book a friend wrote. To the point that I downloaded the photo and magnified to see. I had this idea that it would be Karol’s book and I would write the story about what it meant to see her book on that shelf.

Even though it wasn’t her book, I had a happy feeling, knowing that her book is out there still and people read it. I know this because they search the Internet for her and sometimes find that blog post and send me messages. I hadn’t intended that, when I wrote it, but now I kind of love that I have that lasting connection to her through that.

I’ve been reading this book, The Friend Who Got Away: Twenty Women’s True Life Tales of Friendships that Blew Up, Burned Out or Faded Away, and it’s put me in a reflective mood. The essays are so varied, with different friendships and reasons that they didn’t last. One is about a friend who died, but also a friendship that formed around that death – and then faded away again. One “rule” that I’m extracting from all the stories is one I thought I knew already – it isn’t always about you.

In fact, it rarely is.

I think it’s human nature to believe the world revolves around us. Even though we learn as kids (ideally) that people lead lives when we’re not present, that revelation can be hard one. I remember when my stepkids were little. They would spend every-other weekend and one weekday night for dinner with us. Once they excitedly told us about a new restaurant in town (small town, so big news) and we said, yes, we’d eaten there. They insisted we hadn’t, because they hadn’t yet been. They couldn’t quite grasp that we did things when they weren’t around – as if we retired like companion androids to the closet, when not needed.

Eventually, we grow up and realize that other people have complex external and internal lives that have nothing to do with us. And yet, when a friend turns away, we automatically think it must be something we did. Or didn’t do. Most of the time, though, it’s really about them and what they need.

At any rate, it’s a very interesting book and has given me a lot of food for thought. It’s been lovely, too, to return to reading some nonfiction.

I hope everyone has a lovely weekend!